Reflections of the Pinelands by Catherine Floyd

Policy Notes - December 2025

Artificial turf takes center stage, as NJDEP staff present the science behind their policies. Commissioners consider the gaps and implications for the Pinelands. Policy Notes are designed to update the public on the activities of the Pinelands Commission, which have been summarized by Pinelands Alliance staff who attend all public meetings of the Commission.

By Heidi Yeh, Ph.D.December 22, 2025

Inside the Pinelands Commission’s Latest Deep Dive on Synthetic Turf

What NJDEP revealed, what commissioners asked, and what the public had to say.

At the most recent meeting of the Pinelands Commission’s CMP Policy & Implementation Committee, synthetic turf took center stage—not as a shiny recreational upgrade, but as a complicated, often-misunderstood system of plastics, infill, heat risks, ecological uncertainty, and expensive, short-lived infrastructure. The meeting featured two major presentations from New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) staff—one by the Green Acres program, and one by the Division of Science & Research— followed by one of the most engaged rounds of commissioner questioning and public comment we’ve seen in recent years.

You can watch the full presentations by NJDEP staff from The Green Acres program, the Division of Science & Research, and the public comments that followed.

Green Acres: “We Prefer Natural Turf” (But Still Fund Synthetic Turf)

Cecile Murphy of NJDEP’s Green Acres Program opened with a remarkably candid presentation about the program’s history—and present discomfort—with funding synthetic turf, which they refer to as “synthetic turf” rather than artificial turf. Green Acres has been funding synthetic turf for more than two decades, largely because the fields promise “additional playing time” and “minimal impacts from rain events.” She noted that natural grass fields may need several days of downtime after storms, while synthetic fields can reopen quickly.

However, what she did not mention is that drainage issues often associated with natural grass fields are typically due to poor design. Towns could just as well invest in advanced drainage for their natural grass fields, like the DrainTalent or SubAir systems. Murphy’s statement also assumed that artificial turf fields are more prepared to weather a storm—not so, which Ridgewood had to learn the hard way earlier this year, when its artificial turf fields sustained over $50k in damages after receiving less than 2 inches of rain in July.

But Murphy made it clear: Green Acres is not convinced by the sales pitch, stating, “We’re not really sold on the idea that synthetic turf is low-maintenance. There seems to be a lot of maintenance involved that isn’t discussed upfront.” And maintenance isn’t the only concern.

Short Lifespan, High Cost

Synthetic turf warranties typically last 8–10 years. With exceptional maintenance, a field might make it to year 12 or 15, but that’s still far below the 20-year minimum Green Acres expects for most major investments. That means many towns are already coming back to NJDEP to seek funding to replace the surface long before expected.

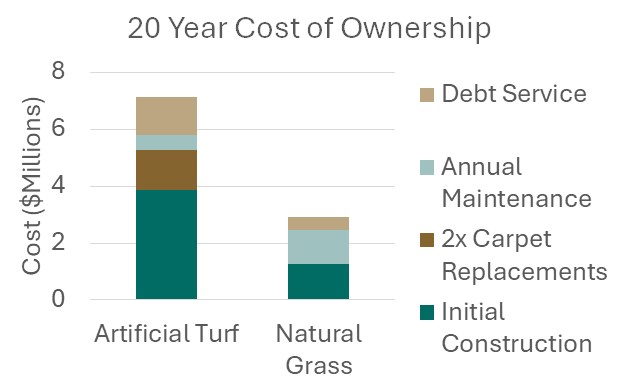

The presentation did not really delve into the actual costs of artificial turf fields, which are over twice as expensive to own, even when the higher maintenance/staffing costs of natural grass are accounted for. We broke down the costs in our webinar: watch the recording here. But here lies one of the biggest issues with Green Acres funding: the program will fund capital investments, but not ongoing maintenance costs. The higher cost of artificial turf installation will be covered, but the higher cost of annual maintenance for natural grass will not. Therefore, elected officials may be viewing artificial turf as a way to shift their costs onto state taxpayers, rather than their own budgets. Green Acres willingness to fund a more expensive option like artificial turf creates a moral hazard that could be influencing towns to choose plastic instead of natural grass, even though the latter would be half as expensive to taxpayers.

Public Access Problems

Because synthetic turf is expensive to install and costly to repair, many towns try to protect their investment by fencing fields off. Murphy noted:

“Applicants tend to fence them off… but what that means is the general public doesn’t get to get on the field.”

For a program whose mission is public access, this is a serious issue.

Environmental Justice: A Double-Edged Sword?

Green Acres struggles with a difficult equity question. Urban communities desperately need high-quality recreation space, and placing natural grass fields in dense areas is nearly impossible. Yet those same communities are already overburdened by environmental harms—and synthetic turf comes with externalities: heat risk, microplastics, disposal challenges, chemical exposures, and more. The environmental justice argument has been used to justify the installation of fields at FDR Park in Philadelphia, but residents have been taking the city to court over this decision.

Murphy pointed to communities with high populations of immigrants as areas of high demand, with many coming from countries where soccer is huge. So why not learn from these soccer fans?

The European Union has banned the use of crumb rubber on artificial turf fields—the most common type of infill used for artificial turf fields in the U.S.. Dutch Professional Football no longer allows artificial turf—only fully natural or hybrid fields. Hybrid fields are natural grass and soil reinforced with artificial fibers that can constitute no more than 5% of the playing surface—a 95% reduction in the plastic, even before accounting for infill.

FIFA has not banned artificial turf (even after players sued them for using artificial turf in the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup), the organization now seems to prefer or require natural or high-quality hybrid pitches for elite matches and stadium licensing—such as the upcoming 2026 FIFA World Cup Final, for which MetLife Stadium’s artificial turf is being ripped out.

Due diligence: Escalating Requirements

To provide some measure of education and assess how much thought has been put into the ramifications of each proposal, Green Acres started requiring a synthetic turf addendum in 2023, and even more is coming in 2026. Applicants must now:

- Analyze heat-risk mitigation.

- Prepare public engagement plans.

- Offer alternative analyses comparing natural vs. synthetic turf.

- Demonstrate planning for end-of-life disposal.

- Show how they’ll replace fields without state funding, since Green Acres will not refund a project within 20 years.

However, we have OPRA-ed (Open Public Records Act) many of these responses and found their answers to be lackluster. In many cases, greenwashed claims from the artificial turf industry are often repeated. The questions have the applicant focus on their plans to mitigate the harms of artificial turf, but do not challenge the applicant to consider what they could achieve by making a real investment in their natural grass fields.

NJDEP Human Health and Environmental Review: “Generational Progress,” Persistent Unknowns

Next, Greg Raspanti, Ph.D., MPH, walked the Commission through the state of the science—starting with the Federal Research Action Plan (FRAP), a study conducted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, it should be noted that these studies have been criticized by the group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), which has asserted that the agency had no scientific basis for downplaying toxic exposure risks associated with crumb rubber.

Raspanti did note that the research is lacking because it is difficult to get the organizations that own these fields to agree to participate in studies, saying: “I think a lot of people are hesitant to engage in these projects when they already have a turf field installed because they might not exactly want to know what’s there, and then bear the burden of cleaning it, or fixing it, or disposing of it.” Ignorance is bliss, after all.

Chemical findings

Testing on recycled tire crumb rubber (RTCR) from dozens of fields found detectable levels of: 20 of the 21 metals that they tested for, 37 of 39 semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) that they tested for, and PFAS.

Although they acknowledged the presence of an array of contaminants in artificial turf fields, NJDEP staff repeatedly emphasized that the levels that were detected did not exceed a threshold that they would find concerning. The dose makes the poison, so it is important to contextualize the actual levels of harm that are expected. However, NJDEP staff consistently emphasized that they are comparing the artificial turf contamination to a non-residential standard. Since children are probably only spending a few hours on these fields per week, they argued that this less stringent non-residential standard was more relevant than a stricter residential standard.

However, parts of the field do come home with players, both unintentionally (stuck to bodies and clothing) and intentionally, as people seem to be purchasing spent turf carpet on Facebook Marketplace to bring into their homes. The exposure to artificial turf pollutants is more intimate than the researchers seem to be aware. This is a lesson that some soccer goalkeepers have been learning the hard way, as reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer. Elevated cancer rates among the players who undoubtedly spend the most time in contact with the synthetic turf should give everyone pause.

Heat: 59 degrees hotter

Synthetic turf can be nearly 60°F hotter than natural grass under the same conditions. Raspanti noted that many variables influence heat injuries beyond temperature, but ultimately conceded that:

“Yes, you absolutely can expect increased heat injuries.”

Most mitigation strategies hinge on hydration, shade, rest breaks, and limits on strenuous activity. Realistically, will the players actually receive these protections? Public awareness of the heat threat posed by artificial turf remains low.

Raspanti downplayed the impact of these hotter surfaces, saying “the effects are very minimal compared to other urban infrastructure.” True—artificial turf has similar albedo (how much sunlight it reflects) to asphalt—but that’s why we are trying to reduce this kind of material and replace it with truly green infrastructure.

Natural grass that is 60°F cooler than the surrounding environment makes a huge difference to players who are exerting themselves on these fields. This would have made a difference for the 160+ people who had to be treated for heat exhaustion—with some hospitalized—after graduation ceremonies that took place on an artificial turf field in Paterson, NJ, in June.

Testing for Bacteria

Testing also found Staphylococcus aureus on 42% of fields and MRSA on 70%—survival varies by conditions, but cleaning protocols are recommended. Combine this higher load of harmful bacteria with the increased abrasion from “turf burn” (when skin comes in contact with artificial turf), and you have a recipe for more infections. This could be the reason why NFL players suffer from MRSA infections at 400x the rate of the general population.

Microplastics: built-in pollution

Raspanti noted that under the commonly accepted definition (under 4 mm), crumb rubber infill is already a microplastic upon installation. Wear, weather, and shoe treads gradually grind these microplastics into smaller particles, which migrate off the field via rain, snow removal, maintenance equipment, and on players’ clothing and gear. Once loose, microplastics can carry attached chemicals into soil and waterways.

Disposal: nowhere to go

With a 10–12 year lifespan and nearly no recycling facilities in the region, end-of-life synthetic turf is piling up. Murphy later confirmed that reuse and recycling options remain “not realistic,” despite industry claims.

Commissioners Dig In: What About the Pinelands?

Commissioners pressed the DEP staff on several critical issues:

- Why use non-residential standards for children?

- How do chemicals migrate over a field’s lifespan?

- What about aquatic toxicity, especially in the sensitive Pinelands environment?

- Where should all this material go at the end of life?

- If newer fields have higher chemical levels, does that mean older fields have already shed contaminants elsewhere?

Commissioner Rittler-Sanchez raised the precautionary principle directly:

“Are we considering the principle of first doing no harm… especially to children and ecosystems?”

Murphy responded by emphasizing competing public goals—access, equity, recreation—while acknowledging the environmental tradeoffs.

Commissioner Lohbauer urged NJDEP to conduct watershed-specific studies, pointing out that the Pinelands’ acidic soils and unique hydrology could alter the mobility and impacts of contaminants.

Public Comment: Plastic Pollution, Turf Science, and Lived Experience

The public comment period was unusually robust. Speakers included:

A natural turf farmer:

Alan Carter of Tuckahoe Turf Farms described the evolution of natural grass, highlighting new varieties requiring fewer fertilizers and pesticides. Modern natural turf, he argued, is a very different product than what existed 20 years ago.

Anti-plastics advocates

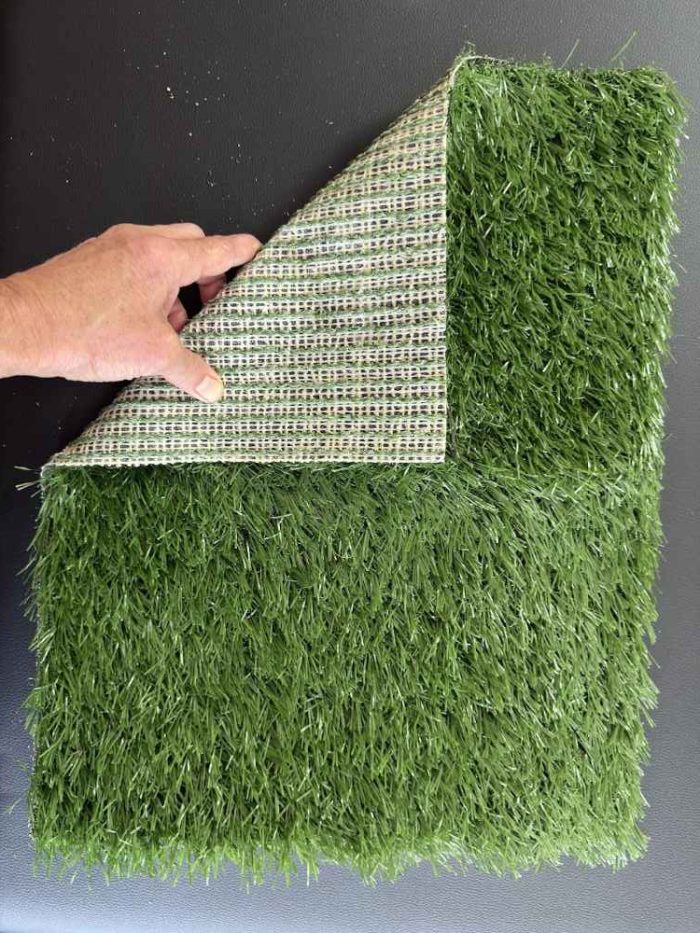

Jean Lehmberg from Beyond Plastics offered an eye-opening “show and tell” on the plastics used to manufacture turf fields. Each one requires approximately 40,000 pounds of plastic, which is equivalent to millions of plastic bags, bottles, and straws. Her props included a pound of crumb rubber that could be picked up by the handful coming off the Houlihan/Sid Fey fields in Westfield (Union County).

Jean Lehmberg from the group “Beyond Plastics” shows Commissioners real-life examples of artificial turf components, including the plastic carpet that must be replaced every decade, pre-production nurdles that are used to create the plastics, and crumb rubber that is used as infill.

Photo credit for prop photos: Jean Lehmberg

Greg Lehmberg shared these photos with Commissioners from the artificial turf field at Kehler Stadium in Westfield (Union County) that showed microplastics migrating off of the field into the surrounding streets and stormwater systems, clearly not being contained by whatever catchment systems are supposed to be in place:

Environmental organizations

Pinelands Alliance staff emphasized:

- Microplastic mobility in the Pinelands

- Heat risks ignored in “365-day play” claims

- Lack of comprehensive research in the region

- Rising grassroots opposition as communities learn what’s in these fields

Sierra Club NJ Chapter representatives highlighted that many municipalities lack qualified natural grass managers—leading to degraded fields and quick decisions to install synthetic turf when maintenance, not materials, is the problem. Hiring a certified sports field manager, they noted, costs a fraction of installing a synthetic field.

Where We Go From Here

The Pinelands Commission must be examining these environmental questions because municipalities are not. In many cases, there isn’t even public awareness or discussion of the pros and cons involved with artificial turf fields, which are often buried in large spending packages. The artificial turf fields are not given the scrutiny that they require when hidden behind attractive budget items. For example, Southampton Township residents were sold an artificial turf field that was packaged under a Pre-K program—that is, if they even noticed the field vaguely described as “turf”.

Public debate focused on the Pre-K funding question and the misguided proposal to remove a solar array that is not even halfway through its useful life. Facing a deadline to utilize state funding for Pre-K expansion, other package items like the artificial turf slid under the radar.

If this meeting showed anything, it’s that the Commissioners are asking the right questions. The challenge now is ensuring state policy, local planning, and community awareness keep pace with the science.

When all of the indicators point to harm, and the best that the science can offer is uncertainty, we should follow the advice of the Children’s Environmental Health Center of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which “strongly discourages” the use of these artificial fields.

The Pinelands deserve answers. And until we have them, the precautionary principle isn’t just wise—it’s necessary.

Months since the Pinelands Municipal Council last met: 38 months.